Taylor has long been regarded as a frequently highly effective ‘jailhouse lawyer’ and LawFuel is aware that one of the country’s leading judges believes he is a more accomplished advocate than many lawyers who appear before the Judge.

With 38 years behind bars and over 150 convictions for serious offences including aggravated robbery, fraud and drug offences. He has also escaped from custody on a dozen occasions.

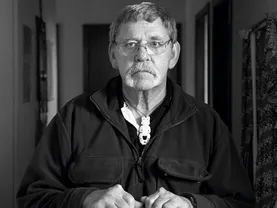

Among his numerous legal successes has been the 2016 private prosecution he brought against ‘Witness C’, who had given evidence against David Tamihere, (pictured) the man convicted of a double murder of Swedish tourists.

Among his numerous legal successes has been the 2016 private prosecution he brought against ‘Witness C’, who had given evidence against David Tamihere, (pictured) the man convicted of a double murder of Swedish tourists.

Witness C was found guilty on eight perjury charges.

Taylor may only appear in cases in which he has personal involvement, but has taken the prisoner voting ban action in 2010, leading to the decision (see the press release below).

In 2010 he also took a case involving a prisoner voting ban when Justice Murray Gilbert ruled that the ban, which by then had been in force for 17 months, was “unlawful, invalid and of no effect.’

In 2013 TVNZ and other media outlets requested permission from the Corrections Department to interview Taylor in prison. Corrections declined, claiming there were security risks involved and in 2015 Taylor took the case to the Court of Appeal which ruled that the interview could proceed. In his decision, Justice Harrison said there were numerous mistakes in the Department’s decision to refuse the interview and said Corrections apparently did not want to give Taylor a “voice”.

The Supreme Court Decision: ATTORNEY-GENERAL v ARTHUR WILLIAM TAYLOR & OTHERS

In issue in this appeal is whether the High Court has jurisdiction to make a declaration that legislation is inconsistent with the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 (the Bill of Rights). The Bill of Rights is silent about the remedies available for inconsistent action.

The present case arose in the context of the prohibition against prisoners’ voting introduced by the Electoral (Disqualification of Sentenced Prisoners) Amendment Act 2010 (the 2010 Amendment). Mr Taylor and the other respondents sought a declaration that the 2010 Amendment is inconsistent with the right to vote expressed in section 12 of the Bill of Rights.

This declaration would not affect the validity of the 2010 Amendment. The High Court found the jurisdiction to make such a declaration exists as part of the Court’s role of providing remedies for breaches of the Bill of Rights and granted the declaration.

The Attorney-General appealed. The Court of Appeal concluded that the Court had jurisdiction to make a declaration of inconsistency and so dismissed the appeal. However, although upholding the declaration made by the High Court, the Court found that Mr Taylor, a long-serving prisoner, was disenfranchised by the previous legislation and not the 2010 Amendment.

On this basis, the Court of Appeal said he therefore lacked standing to apply for the declaration of inconsistency. The Supreme Court granted the Attorney-General leave to appeal on the question of whether the Court of Appeal was correct to make a declaration of inconsistency and to Mr Taylor on whether he had standing to seek a declaration.

The Human Rights Commission was granted leave to appear to make submissions.

The Supreme Court’s decision A majority of the Supreme Court, comprising Elias CJ and Glazebrook and Ellen France JJ, has dismissed the Attorney-General’s appeal confirming there is jurisdiction to make a declaration of inconsistency and upholding the decision to make a declaration. The Supreme Court has also unanimously allowed Mr Taylor’s cross-appeal with the result that Mr Taylor has standing.

Glazebrook and Ellen France JJ took as their starting point the need to provide a remedy for action inconsistent with the Bill of Rights in order to ensure the Bill of Rights was effective. The courts could draw on the ordinary range of remedies to provide a remedy and that included a declaration. They observed that the Bill of Rights applies to the legislative branch and that there would be no other effective remedy available in the present case.

The argument on behalf of the Attorney-General that making a declaration did not fit with the ability to legislate inconsistently with the Bill of Rights was accordingly rejected. Glazebrook and Ellen France JJ further noted the making of a declaration of inconsistency was consistent with the role of the courts to make declarations as to rights and status. Glazebrook and Ellen France JJ considered there was utility in the declaration sought as providing a formal declaration of prisoners’ rights and status. A declaration may also be of use where a claim is made to the United Nations Human Rights Committee in the context of a challenge under the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. On this basis, they did not accept the submission made on behalf of the Attorney-General that making a declaration of inconsistency did not fit with judicial function.

Elias CJ largely agreed with the reasons of Glazebrook and Ellen France JJ. Elias CJ said that the availability of declaratory relief followed from the scheme of the Bill of Rights and its requirement that the rights in the Bill of Rights apply to acts of the legislature and to the judicial branch. The Chief Justice considered that the question of consistency of legislation with rights is a question of right which the Court can answer and that the declaration of inconsistency was a declaration of right. A declaration recognised and vindicated the plaintiff’s right to vote while not interfering with Parliament’s ability to legislate in this way.

William Young and O’Regan JJ dissented. While accepting that the declaration of inconsistency could be consistent with judicial function, they considered there was no utility in granting a declaration because it would not affect any legal rights. This distinguished the New Zealand context from other countries where the jurisdiction was expressly provided for by legislation and further legal consequences, such as requiring a Minister or public official to draw the inconsistency to Parliament’s attention, flowed from the declaration.

The Court unanimously allowed the cross-appeal. That was primarily on the basis that, in the context of a case about the jurisdiction to grant a declaration, Mr Taylor had sufficient standing because the 2010 Amendment expressly continued the prohibition on voting for long-term prisoners.

Source: Lawfuel.co.nz, November 9, 2018, 1:10 am